A Brief History, How It Began

This part of Bucks County is steeped in Colonial tradition. John Fitch, the inventor of the steamboat, lived nearby. Congressman Robert Ramsey was born in Warminster Township. Colonel Joseph Hart who played a pivotal role in the revolution, lived in Warminster in a house built in 1750 by his father John Hart .

In 1777, General Washington had his headquarters at The Moland House in Hartsville, where it is believed that the “Betsy Ross” flag was first flown. His army passed through on York Road several times and Washington stopped over at the Hartsville Inn on several occasions, traveling between Philadelphia and Coryell’s Ferry (New Hope). The action of the Battle of Crooked Billet took place just south of the Borough; the territory of what is now Ivyland was part of the area covered by forces under the command of Brigadier General John Lacey Jr., of Bucks County, given the responsibility of preventing local supplies from reaching the British Army in Philadelphia.

Edwin Lacey was a relative of the Revolutionary War general and the son of Isaac and Ruth (nee Twining). Lacey was a tall, gaunt, red-headed bachelor, a Quaker, and a farmer. He was an abolitionist, a total abstainer from alcoholic liquors, tobacco, and profanity.

The Lacey family in America descended from William Lacey, who came from the Isle of Wight in the 1600’s, and settled in Wrightstown, Bucks County where Lacey lived with his sister.

Early in the 1870’s, Lacey sat talking in the farm house of his friend William Kirk, at the corner of Jacksonville and Kirk Roads. He remarked to Kirk that he had some money to invest, and was intrigued with the thought of making a profit on the forthcoming 1876 Centennial Exposition, to be held in Philadelphia. He foresaw thousands of visitors, and considered that a big hotel situated in the country a short distance outside the city, should attract overflow, transient travelers, as well as a goodly portion of those who wished to live outside the city during their visit. It would also serve as a stop for visitors coming to the Exposition by rail from New York.

Kirk pointed diagonally northward across Jacksonville Road, and remarked that there was the ideal location. The area was then in Warminster Township, and it consisted of 105 acres of land, part of a tract ceded by William Penn to Joseph Hart in 1719. In 1810 Joseph transferred it to Thomas Hart, from whom John Hart acquired it in 1840. In 1850 John willed the land to Joseph Hart. In 1859 it passed to Thomas Wynkoop who purchased it from the Hart estate.

In 1872, the year previous to the conversation between Kirk and Lacey, Isaac Parry had purchased the land from Thomas and Elizabeth Wynkoop. The plot pointed out by Kirk was the western portion of Parry’s farm, just across Jacksonville Road. One advantage loomed large for Lacey. The plot bordered on the proposed extension of the North Penn Railroad, which had just extended its tracks from Glenside to Hatboro in 1872. There was talk of continuing three miles more to the Bristol Road, and eventually, on to New Hope.

On June 24, 1873 Lacey purchased 40 acres of land from Isaac Parry, roughly a square, on the western side of Parry’s farm, extending from Jacksonville Road to the line of the proposed railroad. On this quadrangular plot Lacey planned his village, much as a modern developer might do, laying out streets, and establishing a type of zoning unusual for the time. Ivyland is probably the first regularly planned town in Bucks County!

Four broad streets were to run West from Jacksonville Road, these to be crossed by four streets running north and south. Lacey’s friend Kirk questioned the unusual width of the planned streets, no doubt considering the extra ground thus utilized as wasted. But Lacey was visualizing a beautiful village, with, possibly, horse cars moving along the streets for transportation, a thriving town with, later, industries to solidify it.

The east-west streets Lacey named for public figures whom he admired. Wilson Avenue was named for Henry Wilson, noted abolitionist and war-time Senator, who had just been elected U.S. Vice President. Gough Avenue received its name for John B. Gough, the temperance lecturer. Lincoln memorialized the slain president. Chase Avenue was named for Salmon P. Chase, of the Lincoln cabinet, later Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. The North-South street, Twining, was named after Lacey’s mother, whose maiden name was Ruth Twining. Dubois was named for a personal friend of Lacey. A third was originally named Mason Avenue, probably for the fraternity of Freemasons, which was forming many lodges during this period. It was later changed to Pennsylvania Avenue. Greeley Avenue was named for Horace Greeley, the abolitionist editor of the New York Tribune, just defeated by Grant for the presidency. Lacey chose the name Ivyland for his dream village after the beautiful, glossy, three-leafed Ivy in which the area abounded; apparently he was no botanist, and did not realize it was Poison Ivy. Thomas MacKenzie, who knew the founder personally, stated that Lacey envisioned lovely ivy-covered walls throughout his town.

The first cellar was dug in August 1873 at 64 Lincoln Avenue; this was the first of his houses completed. The dwellings at 1090 Jacksonville Road, and at 133 Lincoln Avenue were built this year.

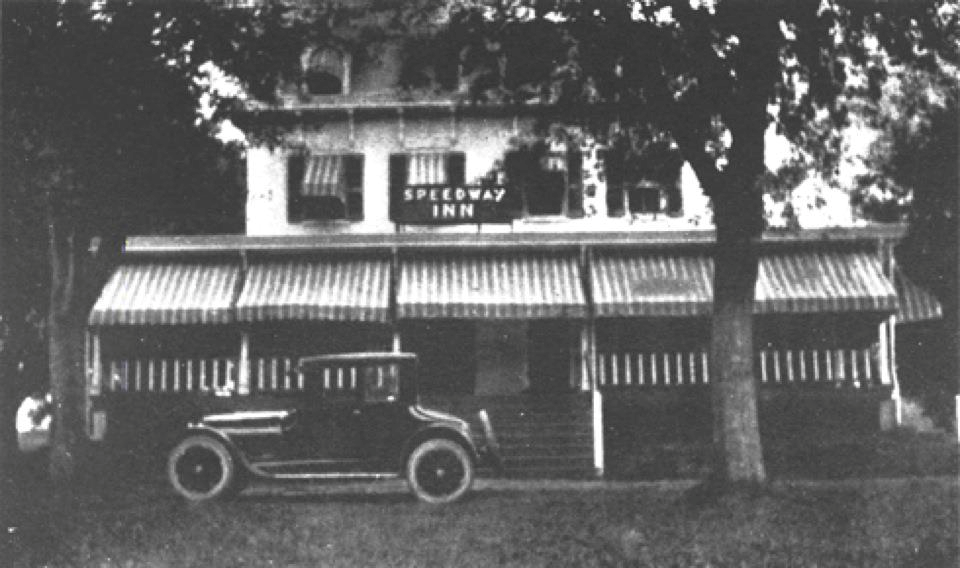

The Temperance House Hotel

Lacey now began to build his hotel. It was a large summer hotel, near the center of his town, a four-story stone and pebble-dash building, with broad, covered porches completely surrounding its first two floors. The roof was the French Mansard style, a type that William Kirk had used on his house, and which Lacey particularly admired. It was required by him on all the first buildings he built in Ivyland, including even the hotel’s brick stable and comfort building. As might be expected, he named it The Temperance House. The actual erection work was done by Joseph A. Carrell, son of Hugh Jamison Carrell. Stone for the hotel was quarried on the farm of Joshua Bennett about a mile northwest of the village.

Construction work proceeded so slowly that the hotel was not completed in time to attract the expected Centennial visitors. This certainly contributed to the financial difficulties which later plagued Lacey. Adjoining the hotel at, 67 Gough Avenue, he built a general store, of frame construction, also complete with his beloved French roof.

Lacey made sure that the first residences his contractors built were all along Gough and Lincoln Avenues, the center of his quadrangle. He also supervised the planting of Silver Maples along his streets; these are fast-growing trees, and he wanted to add to the beauty of Ivyland as quickly as possible.

Troubles beset Lacey from the beginning. Construction on the hotel was slow. One month after work began, the notorious Jay Cooke failure occurred, and a serious depression lasted for several years. As a result building came to a standstill. The hotel thus stood unfinished right through the period of the Centennial Exposition, and all Lacey’s golden dreams of wealth stood unfinished with it. The contractor had no funds, nor would any bank lend money during this period of financial panic. Lacey’s faith in his project remained unshaken and he signed his personal notes to procure material and labor to keep construction progressing. His creditors called for additional funds to cover his loans in the rapidly sinking market, and in 1879 Lacey was compelled to dispose of his Ivyland holdings in order to recover money for his personal expenses. (It appears, however, that the Quaker farmer-turned-developer was down, but not out. He pioneered a similar development in a western state, and in a year or two had a project on the way for which he refused the princely (for then) sum of $25,000!)

The Hotel building was eventually completed, but was never used as a hotel. Joshua Bennett bought the building at a sheriff sale for $2600. William Kirk took over 52 lots on the eastern end of town, Mary Spraglo who owned the adjoining farm to the southwest was another large purchaser, and Samuel Trumbower and John T. Murfit, from Somerton, bought up a large number of lots and in 1879 they resold 86 lots to Joshua Bennett.

Lacey’s anticipation of the railroad was soon fulfilled. On March 9, 1874, Ivyland got its first train service: the line was extended to Bristol Road. Construction help was provided by Samuel Davis whose farm bordered on the right of way between Johnsville and Ivyland stations, where a heavy fill and a creek bridge were needed. Davis supplied the teams for the grading, the stone for the bridge, and lodging for the construction gang while it worked. In return he took shares of railroad stock. The railroad also offered a life-time pass but he declined it, saying “I never knew dividends to be paid out of passes; if I can’t afford to pay my way on the train, I had better stay home.”

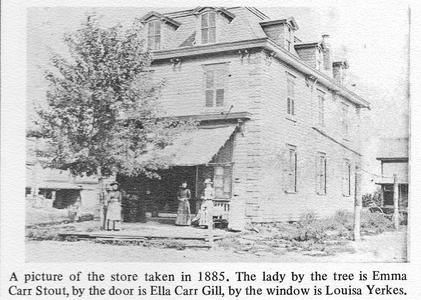

The Store

The frame store built by Lacey next to the hotel was first occupied by J. Montgomery Carr, who previously had a store and dairy establishment at Neshaminy, on Street Road at Easton Pike. He took over the Ivyland store, and occupied the double house to the rear at 64 Lincoln Avenue. He operated the store with his son, Wilmer W. Carr. Success came quickly; Carr’s store became popular for miles around, its fame reaching even to “The City.” Here one could buy anything in the clothing line: boots, shoes, flannels, laces and yard goods. Dress material of pure silk was sold before Wanamakers carried this high grade stock, and it is said that shoppers came from Philadelphia just to buy this fine merchandise. Carr devoted a whole floor to hardware, including a complete line of harness parts, but the major part of his trade was in groceries. At one time he employed half a dozen salesmen, and had four delivery wagons traveling the countryside delivering orders.

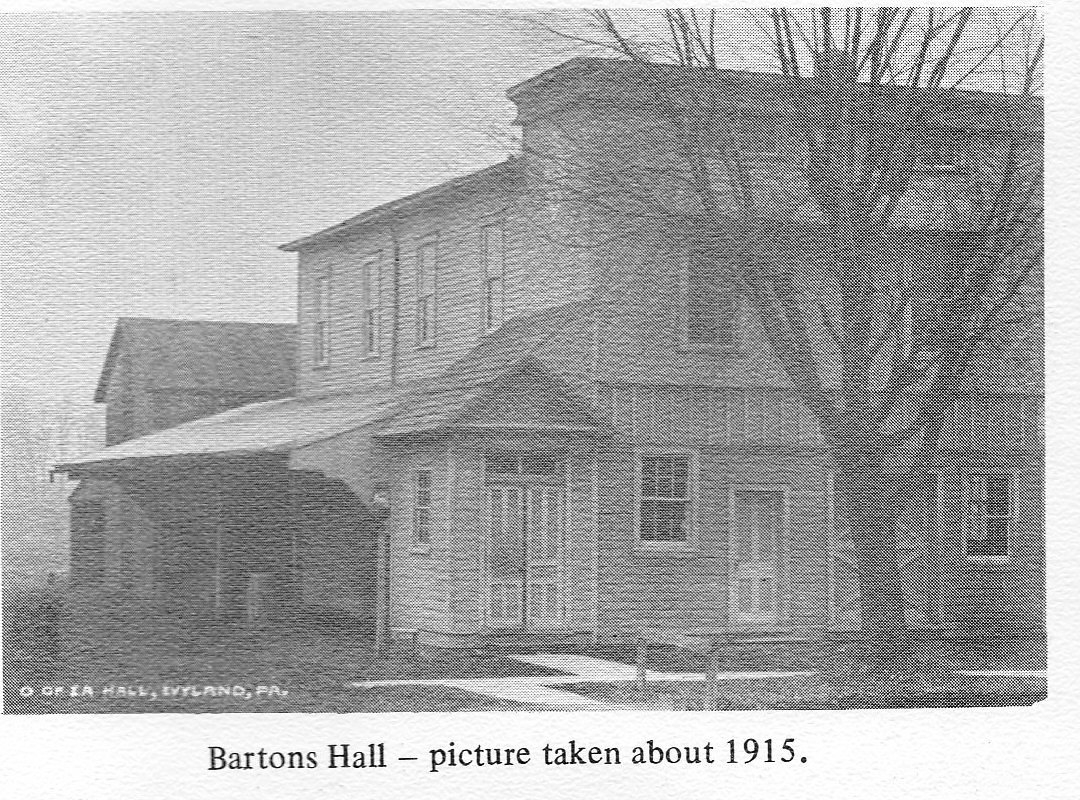

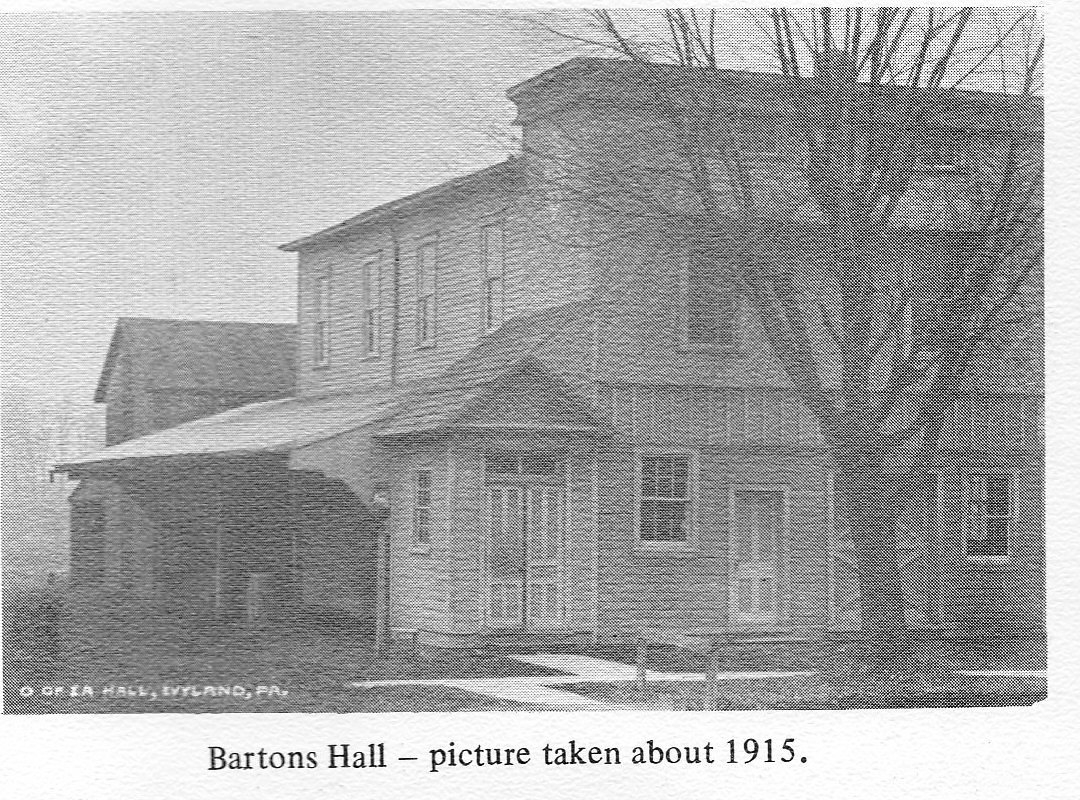

Barton Hall

The Barton brothers were the sons of Robert Barton, who came to Ivyland from his farm on York Road near Jamison. William Henry, built a plant consisting of a sawmill, machine shop and smithy on the southwest corner of Wilson and Pennsylvania Avenues. The second floor of his building had enough room for him to rent meeting places for several lodges. This is the building which for many years served as the Ivyland Borough Hall. It was destroyed by fire in 1998.

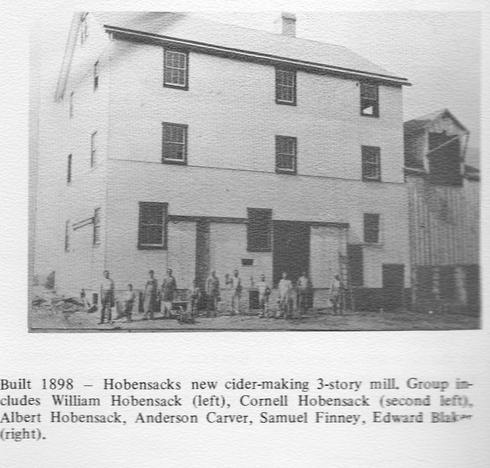

Hobensack’s Mill

When J. Montgomery Carr arrived in Ivyland, he built a coal yard and feed house, in 1874, along the railroad at the end of Wilson Avenue, and he operated this business in addition to the store, for several years. In 1879 he sold this business to William Henry and Harvey J. Barton in order to devote his time to the development of his store. The two Barton brothers conducted the coal and feed business for eleven years and then sold it to William and Frank Hobensack. The Hobensacks increased its scope and were successful in their venture. Frank later entered politics and was elected sheriff of Bucks County, an office he held for many years. In 1899 he sold his share of the business to William.

The U.S. Mail

In the first years of Ivyland, mail came from Hatboro. Soon after the railroad came through to Bristol Road (then called Hartsville station), mail was dropped off there. James Flack, who was then building Breadyville (a small section at Bristol Road and Wilson Avenue), was appointed postmaster. In 1879 G. Krusen Finney, who owned the new Breadyville store, succeeded Flack, and when Finney was made Justice of the Peace, her son Jack took over until 1905 when the Breadyville post office was abandoned.

The Church

Religious observance came to Ivyland almost at the beginning. In May of 1875, Rev. G.H. Nimmo, pastor of the Neshaminy of Warwick Presbyterian Church in Warminster, (then called “The Hartsville Church”) organized a Sunday School, with Silas M. Yerkes as superintendent. Meetings were held in the home of Andrew Bushnell on the southwest corner of Gough and Jacksonville Roads. The Sunday School was a mission of the Hartsville Church, and at first had no permanent home. It met, by turns, in Ryan’s carpenter shop, the hotel, in Lyceum Hall, at the railroad station, again in the hotel, and, finally, on July 4, 1886, in the new Chapel, where it found a permanent home.

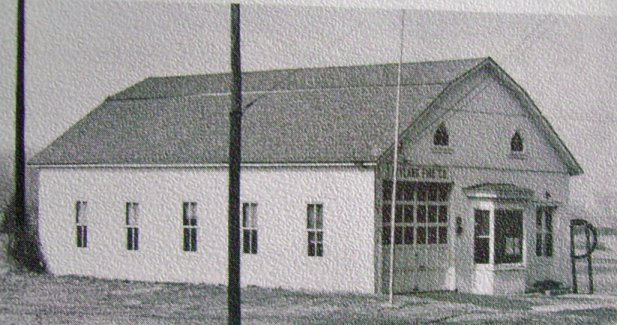

The Fire Company

The Fire Company began in 1886. A supply of fire buckets, canvas, with rope handles, several fire hooks, and a horn for blowing an alarm, were stored in William Henry Barton’s saw mill on Gough Avenue. William Henry Barton was the first Fire Chief. In event of a fire, the alarm was blown, and everybody within hearing would rush to assist. A bucket line would be formed, passing loaded buckets from the nearest water source to the fire.